The Bead as a Metaphor for Life

by Chiori Santiago for Ornament Magazine Winter 2004

A Bali bead is more than a sphere of genuine sterling silver, painstakingly embellished with delicate granulation and fanciful filigree. A Bali bead is a metaphor for a way of life conducted with careful intention, a respect for the magic of art and a commitment to keeping spiritual forces in balance. That is how life is in the Balinese village where silversmiths use centuries-old techniques to produce beads for Nina Designs, an Emeryville, California firm. That is also how owner Nina Cooper approaches her own life, as a constant quest for equilibrium between commerce and art, work and family.

Step inside the spacious studio housing the business to find a low hum of activity as employees take orders over the telephone, tap information into computers or search the rows of red, blue, yellow bins for items to fill a customer’s request. The soft “shush” of beads and findings sliding into plastic bags alternates with the sound of Vila, an employee’s pet pug, trotting from her corner bed to check up on things. Upstairs in the loft kitchen, someone makes a cup of tea.

“It’s an interesting balance,” says Cooper as she surveys the room. “On the one hand, I like it to be relaxed. This is not a very authoritarian environment. There’s no dress code — we’re on the phone a lot, so there’s not a whole lot of makeup, hair and nails going on. The employees tend to be young and very artistic. We have a couple of jewelry designers, graphic artists, a painter and a fine jeweler. We really try to be nice to each other.

“At the same time, the work is extremely fastidious and exacting. Picking out beads and filling orders requires people to be very much into detail and to keep very close records. We can’t make mistakes. If one person drops the ball, someone won’t get their product. So it’s a team effort. We’re all part of the business. It’s like putting on a play — the employees are the actors, and I’m just the director, shepherding things along.”

First-time customers often are drawn by the Nina Designs imaginative advertisements — that fabulous snaking dragon or serene Buddha assembled from hundreds of bead caps, earrings tops, beads and clasps — a memorable assemblage of Cooper’s wares. The quality and the consciousness behind those wears invariably earn their long-term loyalty.

Most beads in the Nina Designs catalog are handmade in Cooper’s own fabrication shop in Bali. They are real Bali beads worked of fine sterling with patterned surface decoration. They are not cast base metal or silver-coated plastic; you will not find gooey black sludge rubbed into their surfaces in imitation of the authentic oxidation that provides contrast on a true Bali bead. Cooper does not cut corners to meet a lower price point; her artisans are equipped with the benches, torches and other tools they need to do their best work.

As she explains in one of the many articles she has penned about Bali and its silver tradition, “By providing meals, we assure that our smiths are well nourished (hungry people don’t do good work). By paying a fair wage, we assure that our employees have a vested interest in seeing the company succeed. By employing women on an equal footing with men, we do our part to empower women in a culture where they are traditionally subservient to men. Some of these issues may seem tangential to quality, but they all add up to a key concept: pride in product.”

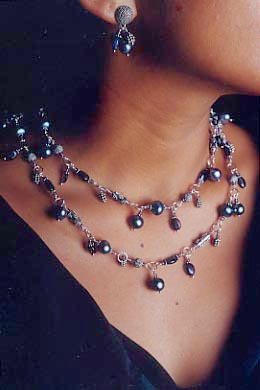

In addition to silver Bali beads, she offers gold reproductions of the classic Bali bead; Thai cast silver beads handset with Swiss marcasite; semiprecious stones from India in silver settings; Javanese filigree beads and pendants; rustic Thai Hill Tribe silver; and a line of cast silver beads of her own design. “We start with traditional designs of those countries, but modify them for our purposes,” Cooper explains. “There are certain lines we won’t cross in term of kitchyness; I won’t do kitties or teddy bears, for example.

“We sell machine-made chain, but handmade is our love. We have a big selection of earring tops, and our specialty is well-designed, well-made, innovative clasps. We provide lots of adjustable options — that was unusual when I started.” Among them: a hook-and-eye closure in which the “eye” is stepped to allow the clasp to lie flush against the skin; and key hole and box clasps, difficult to make by hand. “We were the first to do hidden magnet clasps,” she says, demonstrating how the two halves, male and female, nest so that the clasp will not slide from side to side.

Whenever I’m considering a product I ask myself: Would I use it? If not, why not? What woould make it better?” Like Cooper’s workplace, all the components are designed to live in harmony. “When you do a new collection, it’s not just the bead,” she notes. “It’s the clasp, the bead top, the spacer. There needs to be a visual story a designer can work around. We don’t want to constrain people’s creativity; we want them to express themselves, so we provide a palette for them to work with. We do copyrighted designs, so there are tons of things no one has seen. I don’t put it in the catalog unless I can get excited about it.”

Cooper understands what jewelry designers need because she and her staff are artists as well. “That’s important because everyone understands what the parts are, and what’s important to the customers who call us. They know about proportions, about how an earring should hang. A lot of our customers are pretty much beginners. We’ve coached them through, we recommend substitutions and solve problems. It’s great working with artists, because they’re willing to be creative to find a solution, and they get excited when you get them something they like.

“It’s expensive to staff an office this way, but it’s part of the product we sell. I mean, no one becomes a jewelry designer because they need to be rich. There’s a certain level of devotion to the work on both ends that’s very rewarding.”

She was six years old when she inherited a box of beads from an acquaintance of her mother. “I started making stuff and never stopped,” Cooper says. She made her first sales at a craft fair at age ten, and as a teen sequestered herself in her room to string beaded necklaces. “I was a dancer, and that and jewelry fit together nicely. Throughout high school I carried a shoe box full of jewelry everywhere, and sold a lot of it at dance studios.”

She moved to Berkeley, California at age fifteen and at seventeen got a license to sell her pieces on Telegraph Avenue near the University of California, Berkeley campus. As a student at Berkeley she earned a business degree while performing with the university’s dance company. “I was a fish out of water, but having those two very different sides kept me balanced and sane,” she says. “I got to have my art and not starve. Just to be able to read an income statement and balance sheet — to even know I should have one — put me far ahead of a lot of artists. Selling jewelry on Telegraph Avenue was fun, but when I saw people raising their kids in exhaust fumes, I knew I didn’t want to do that.”

Eventually, she had to make a choice about her next step. “I knew I didn’t want to join a corporation, and I also knew I couldn’t support myself stringing beads in my bedroom.” An invitation to visit cousins in Bali was a convenient way to postpone the decision. “The minute I stepped off the airplane, I sighed. I felt at home in a way I don’t here,” she recalls. “For one thing, the country is physically exquisite, the weather womb-like. And art is an integral part of what they do.” Balinese happily spend as much as a quarter of their time preparing lavishly intricate offerings of fruits and flowers for religious festivals, and the care with which each task is performed is considered more important than simply turning out a final product, Cooper says.

For several years, she imported beadwork, clothing, woodcarvings and textiles from Bali for sale in the United States. In 1991 she lost her home and her entire inventory in the devastating fire that consumed twenty-seven hundred buildings in the Berkeley-Oakland hills. “In a weird way, it was a blessing,” she says. “I had to focus on what to do about the business, and I decided on beads. It was an abrupt transition, but it took off. The time was right. At the time, people weren’t selling parts and components. No one had handmade silver beads. There was no such thing as a Bali clasp; you couldn’t find really good clasps, and they can make or break a piece. Also around that time the bead store craze started.” Supplying retailers with unusual goods remains a substantial part of her business.

At first, when relying on Balinese artisans to fabricate her beads, Cooper’s biggest problem was competing with herself. “In Bali, there’s no such thing as intellectual property. I would spend a lot of time designing a new collection, then go to market and find that someone would have knocked off my designs. The main reason for financing a workshop was so I could produce exclusively my own designs.” Her “closed shop” opened with twenty-five employees. Today, six hundred workers manufacture the jewelry components, giving Cooper great control over product quality. “Even when it’s copied, it never comes out the same as ours, because I use high-grade silver and make sure the smiths have the latest equipment to facilitate their craft, she says. “In the early nineties, the bead wholesale market went crazy. There was tons of junk produced in Bali with watered-down silver, no pride in quality; it was all degraded.

“There always will be people who look for the lowest gram price, but we’ve let that end of the market go, because the people who suffer are the smiths. We price everything by the piece and pay the silversmiths depending upon what it takes to make a particular design — it can be more for a smaller bead. We’re committed to a living wage. When we started, I had to have the workshop location where employees could walk to work. Now most have motorbikes. The smiths in my shop often make more than teachers or doctors, but the result is that customers know they’re buying quality. I can give my word on that.”

For a time, she operated the business out of her living room in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she moved after losing the Berkeley home. She spent much of her time on the road, either selling at trade shows or flying to Bali. “Back in those days, if you had a message for someone over there, you’d have to get on the plane and fly over,” she says. “There was no fax, no e-mail — there was one public phone in the whole village, and half the time it didn’t work.

“There are two reasons why the business is in the form it is now. I realized I liked working with other artists. And I wanted a family, so I moved to mail order for the large part of the business, so as not to have to travel to so many shows.” After adopting her eldest daughter Lyra, now nine, from China, she returned to Berkeley, where she felt the global culture and social acceptance would be a better environment for her daughter. She now has another daughter, Tali, also adopted from China, and is raising both girls with her husband, a professor of business at San Francisco State University.

While Cooper maintains a small jewelry division, she delegates the task of organizing and staffing some twenty trade show booths a year to one of her employees. There are days when she wonders if she has not delegated enough; if this dragon of a business is more than she can handle. “Having a business is like having a child who’ll never grow up and go to college,” she says, smiling. “It’s much easier to start a business than to keep it going. It’s a daily responsibility with a lot of constraints. It’s not just about ‘Do I like my career?’ It’s an awesome responsibility to the craftsmen in Bali and the employees here.”

Then she takes a breath, leaves the studio to walk the labyrinth halls of the warehouse to the back garden. Over the years, the tenants have turned a once-barren expanse of asphalt into a soothing retreat of trees and flowering beds. In the middle of industrial Emeryville, Cooper can remember the philosophy that informs Balinese artisans: that all art is an offering to the gods, that the least significant, inanimate objects are imbued with mystical power, and that life is a constant dance between positive and negative forces.

“I have to remember I’ve created a company that allows me a very good balance,” she says finally. “I have two kids and a manageable work schedule. Often I come up with the most creative solutions just after I put the kids to bed. That’s when I feel I’m doing the right thing, because if you’re doing work that’s contrary to your nature, it’s hard to be successful. You just have to trust that you can figure it out.”